Texas Independence

Precursor to Mexican American War

MEXICAN TEXAS 1821-1836

In 1836, a young congressman's bid for reelection was rejected by the voters. He told his Tennessee voters to "go to hell" and that he was going to Texas.

Davy Crockett then followed the trail of 30,000 American pioneers who preceded him into a huge, sparsely settled territory. The trail Crockett followed had a fifteen year history littered with arrow heads, spent mini- balls and unfulfilled dreams. His decision guaranteed a short life and an indelible place in the pantheon of national heroes.

Texas Independence

National Portrait Gallery

Smithsonian Institution

Historians will note that every "precursor" has a preface. Thus, we begin with Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Americans, never deterred by boundary lines, were crossing into the northeast corner of Texas and claiming that area to be part of Arkansas, and by extension a part of the Louisiana purchase. They created this geographical myth to distance themselves from the reach of Spain's indisputable title to the territory.

Texas Independence

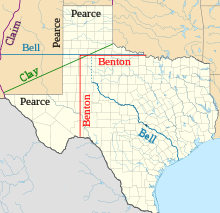

By 1819, when Spain was at war with its Mexican colonials, they were forced to cede Florida to the United States. The agreement (Adams-Onis Treaty) negotiated by President James Monroe's Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, included a northern boundary for Texas at the Red River. Eliminating European power in the Americas may have been a forerunner to the president's later policies embedded in his Monroe Doctrine (1823).

Texas Independence

Red River Boundary 1819

|

Texas Independence

|

In 1811, indigenous Mexican inhabitants commenced an eleven year revolution to gain independence from Spain; much like its northern neighbor in its fight against a European ruler. By 1821, Mexico had gained its freedom and inherited the vast territories of Spain stretching from Texas to the Pacific. They also inherited an intense disapproval of the northern "yanquis" whose language, culture, religion and appetite for slavery were insults to their hosts. The dislike was mutual. The intensity of emotions inevitably became physical particularly when there was the ever present undercurrent pressing for Texas independence.

Texas Independence

Texas Under Mexican Flag 1821

Despite this antipathy toward the Americans, Stephen Austin convinced the old Spanish authorities to grant him the impresario (the right to administer and sell off tracts of land) that initially had been granted to Austin's now deceased father. This was quickly reversed by the newly free Mexican government. From 1821 to 1823, there were a number of similar reversals of Mexican policy. Nevertheless, some limited number of American immigrants had crossed into the Mexican territory . In the space of one month, in 1823, there was a revocation of Austin's rights under Mexico's constitutional monarch, Augustin I. When he abdicated, immediately thereafter, the new government reinstated the impresario---a welcome mat for a new wave of American immigrants.

Texas Independence

Texas state Library and Archives |

National Palace |

Possibly, the Mexicans viewed the Americans as a buffer against marauding Indians and some security for the few Mexican ranches when they granted Austin colonization rights along the Brazos and Colorado rivers. In reality, by that new grant, the Mexicans were shrinking their own borders by almost 100 miles south of the old Red River line.

Texas Independence

By 1829, Austin had "imported" more than 1,000 American families. A small number when compared to the other Americans illegally crossing Texas borders. Lines on a map were no barrier matched against pioneer dreams. The door was open for legal, limited immigration, but the Mexicans deluded themselves when they exacted a promise from Austin that immigrants must become citizens of Mexico and embrace Catholicism. Austin strengthened his position with local authorities and married the governor's daughter.

Austin would remain faithful to his promise recognizing Mexican sovereignty, but to Americans the oath was more honored in its breach. However, by 1834, Austin's fidelity to the central Mexican authorities had met its limits; swept aside by the tide of events that included his several months imprisonment in Mexico and the dictatorship of Santa Anna that extended the control of the central government.

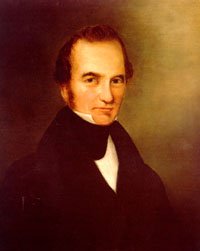

As a new decade opened, there were about 5,000 Mexicans and an indeterminate number of Indians as permanent inhabitants of Coahuila y Tejas, the territorial extension of an existing, northern Mexican state and the territory of Texas. The Indians, mainly Comanche and Apache, had been raiding American homesteads since 1820. Americans felt that the Indians were in league with the Mexican government, but the 25,000 American settlers out numbered and out gunned them. Mexican president, Anastasio Bustamante, in 1830, attempted to close the border and reinstate central authority from Mexico City. He also insisted that Americans register their weapons. Compliance was nil. Immigration was officially halted.

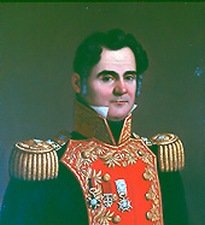

In 1832, the Mexican republic was beset with a series of internal revolts. General Anonio Lopez de Santa Anna surfaced to lead mutinous troops against Bustamante. This led to the abdication of Bustamante and installation of another figure head as president. However, events across the Rio Grande caused Mexicans to turn their attentions to the American problem.

Texas Independence

Bustamante

|

Santa Anna

|

The trouble that began in northeast Texas was unrelated to Texas independence. American settlers favored stronger powers for the individual Mexican states, and aligned their interests with the Federalist forces seeking to unseat the central authorities in Mexico City. Effectively, supporters of General Santa Anna who proposed to reform the government when he took power. This precipitated a clash between the settlers and the central government's Mexican troops garrisoned at Anahuac, an important transit point on Galveston Bay.

On June 10, 1832, the fort was commanded by a former American citizen, Juan Davis Bradburn. He was a zealous supporter of the central government and despised slavery which was outlawed by the Mexican Constitution A local issue arose regarding escaped slaves from Louisiana. Bradburn believed every incident involving Americans was a plot aimed at Texas independence, and usually overacted inflaming the passions of American settlers.

Bradburn arrested the two legal representatives of the putative slave owners. One agent was the attorney, William Travis, who three years later was the American commander at the battle of the Alamo. The arrest was effected without a warrant and promised a prosecution without jury. These rights, cherished in the United States, were not protections afforded Mexican citizens. Nevertheless, Americans believed those rights were mobile and inalienable. Shots were exchanged with the American supporters of the lawyers without any calamitous affect. However, it led to Bradburn's replacement by his superiors.The stage was set for the law of unintended consequences.

American slave owners in Texas cleared the Mexican constitutional hurdle by declaring slaves to be indentured servants, and with similar prejudice, later framed the Texas war as a fight that pitted whites against the browns.

History is not static and even inconsequential events will have unintended consequences. A group of Americans erroneously feared the worse case scenario by events at Anahuac. Their mission was to save the imprisoned Americans. Their response was to transport a cannon to relieve the Americans in Anahuac. Their boat on the Brazos River was stopped by the Mexican garrison at Velasco on June 26, 1832. A fire fight ensued and there were casualties on both sides. The fort surrendered to the Americans. Blood was shed that lit the fire of a rebellion which some Americans compared to Lexington in the American Revolutionary war.

By August 1832, skirmishes were frequent. Three hundred American men were engaged in a daylong battle that was concluded when Jim Bowie captured a Mexican colonel. That day 47 Mexicans perished along with four "Texians".

At this point there was open talk about Texas independence. Although a minority of Americans believed the best path was incorporation of Texas as a Mexican state. Sam Houston, former Tennessee governor, and veteran ally of Andrew Jackson, openly began to seek annexation by the United States. Settlers demanded that Stephen Austin seek aid from Louisiana. The activity and friction created by American pressure had all but eliminated Mexican military authority in northeastern Texas.

In October 1832, settlers called a convention in San Felipe de Austin. Notably, Mexican settlers were excluded. They drew up a petition to be presented to the Mexican government which called for Texas to be an independent Mexican state (separated from Coahuila State), repeal of immigration restrictions and the right to form an armed militia. The Mexican government, in an effort to appease, approved lifting immigration restrictions and decreed English was legal as a second language. These minimal reforms appeared to temporarily satisfy the Americans.

In April of 1833, a second convention was called which essentially duplicated the demands of the prior year. Coincidentally, Santa Anna was elected President of Mexico. This was the first of eleven times that he served either as president or dictator. None of the terms were consecutive and usually lasted for months.

The latest American demands were to be carried by Austin to Mexico City but first were routed through the local Mexican administrative departments. Finally, in 1834 Austin reached Mexico City where he was summarily arrested for treason and held on bond well into 1835. In that year, the Mexican congress granted some redress for settler grievances. However, the appeal for an independent state was not on the Mexican agenda, but a serious cholera epidemic was.

In 1835, Santa Anna became Dictator after defeating Mexican Centralist forces. His previous dedication to federalist ideals (local self rule) was scrapped. He dispatched a 1400 force north to deal with revolts in its northern states and particularly the Americans in Texas.

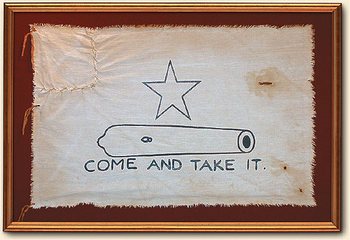

On October 2, a small Mexican force was dispatched to Gonzalez to recover a cannon loaned to the Americans years before to defend against Indian attacks. The Americans led by James Fannin, a former West Point cadet, refused and commenced an attack resulting in two Mexican deaths. The skirmish is considered significant as the first attack mounted against Mexican army regulars. More significantly was the location of Gonzalez. It was located 250 miles west of the eastern areas that heretofore were the hot bed of American resistance. The Texians (as they referred to themselves mixing Mexican and Texan) home made battle flag reflected their attitude and rejection of Mexican demands.

Texas Independence

Courtesy of Gallery of the Republic Austin

Texas Independence

James Fannin

Dallas Historical Society

Before October closed, Austin marched a small force near the village of San Antonio lying about 75 miles west of Gonzalez. In a series of skirmishes led by James Fannin, about two miles from San Antonio, a small number of Mexican soldiers were killed.

In November, Fannin, acting with William Travis, conducted small raids that included attacks on Mexican supply parties. Fannin was actively campaigning for a standing, regular army. Commissioned as a colonel, he continued to lead a mixed group that included irregulars who proved to be ineffective. He found that instilling formal army discipline was problematic, and a drawback to performing his missions.

On November 3, 1835, a fateful convention was convened in San Felipe de Austin. The Declaration announced its opposition to Santa Anna supported by armed Texians. The document was the closest expression of independence to that date, but still expressed ties to Mexico as stated in its opening text:

"Whereas, General Lopez de Santa Anna and other military chieftains have, by force of arms, overthrown the federal institutions of Mexico and dissolved the social compact which existed between Texas and other members of the Mexican confederacy; now the good people of Texas, availing themselves of their natural rights,

SOLEMNLY DECLARE:

1st. That they have taken up arms in defense of their rights and liberties which were threatened by the encroachments of military despots, and in defense of the republican principles of the Federal constitution of Mexico of 1824".

By January 7, 1836, a provisional, operative government was in place.

On November 4, James Bowie skirmished with Mexicans at the gates of San Antonio and by December 4, the Mexicans retreated to the Alamo Mission and were subjected to an American bombardment for five days. The garrison surrendered having suffered over 300 dead; Texians casualties included 20 dead. Americans assumed control of San Antonio by January 1836 with an immediate dispute over leadership between Bowie and Travis. The former, a militia man, would not take orders from Travis a regular army officer. A compromise established them as co-commanders. Shortly thereafter mother nature resolved the argument. Bowie was bed ridden suffering from tuberculosis.

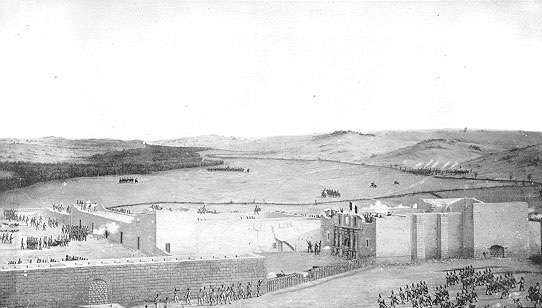

By February of the new year, a call for reinforcements for the Alamo reached settlements north of San Antonio Bexar. On February 26, Fannin had organized a relief column that was so disorganized it never reached San Antonio which would fall to the Mexican army on March 6 (below).

March 19 marked Fannin's short life. He and his force fought a defensive battle at Coleto Creek. Mexican General Urrea attacked with overwhelming force forcing his surrender. Urrea sent word of his victory to Santa Anna and requested clemency for the American prisoners who were marched to the Mexican base at Goliad.

Santa Anna had promised a reign of terror and rejected the request. The prisoners were shot to death. Fannin was the last to be executed. His few, simple last requests were denied. They burned his body marking the 32 year life span of Fannin in the "Goliad Massacre".

Texas Independence

Bowie

|

Travis likeness produced subsequent to his death. |

ALAMO

1836

The Texians were celebrating their independence, but Santa Ana had other plans. He massed 6000 men in northern Mexico (Saltillo) intent on invading Texas. In his fury, he had a message for the United States:

"IF THE YANQUIS INTERFERE WHEN I PUT DOWN THE REVOLT, I WILL ANNIHILATE THEM AND PLANT THE MEXICAN FLAG IN WASHINGTON, D.C."

On February 23, 1836, large advance elements of the Santa Anna forces were spotted approaching San Antonio. The Texians withdrew behind the walls of the old Alamo monastery. Mexicans approached under a white flag to demand surrender and, in an unusual action, received fire from the Alamo Whereupon the Mexicans raised a red flag signifying battle with no quarter, with mercy to none. Americans were immediately subjected to a 13 day heavy bombardment of cannon and howitzers. Their messages sent to Sam Houston and Fannin for reinforcements were to no avail. Houston was too far and Fannin's convoy had failed and he was otherwise occupied at Colato Creek. Nevertheless, some few volunteers were able to slip into the Alamo.

Travis's famous last words in a message sent asking for reinforcements:

"---I shall never surrender or retreat-----I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible and die like a soldier-------Victory or Death".

On March 6, a full scale attack was mounted by the Mexicans. They successfully scaled the north wall and hand to hand combat followed. Crockett, out of ammunition, used his musket as a club, Travis was killed loading a cannon, Bowie, the prodigious knife fighter, arose from sick bed and fought like a tiger. Mexican civilians who witnessed the battle were stunned at the courage of the defenders. Santa Anna showed no mercy. He executed the survivors and burned the bodies in a large funeral pyre. Among the fallen were Europeans, some Mexicans, two Jews and two Blacks.

Texas Independence

Fall of the Alamo

Theodore Gentilz

Texas State Library

TEXAS INDEPENDENCE 1836

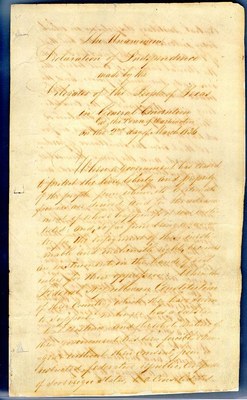

On March 2, 1836, just days prior to the fall of the Alamo, Texians met at Washington on the Brazos (River) and declared Texas Independence. David Burnet was appointed provisional president of the new republic and Sam Houston, leader of the army.

Texas Independence

|

Texas Flag 1839

"Burnet Flag"

|

In the United States, Americans were outraged at the massacres at the Alamo and Goliad. The army that Sam Houston led, 800 strong, kept that message alive. Although they kept dodging the larger Mexican forces, Houston, a fine tactician, found an opening at San Jacinto (April 20). Houston's men took advantage of the Mexican (Spanish) tradition of siesta and got within 200 yards of their camp before discovery. Too late for the Mexicans to recover. The battle was over in 18 minutes. His men had charged yelling, "Remember the Alamo" and "Remember Goliad"

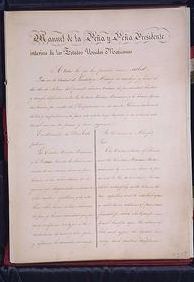

Santa Anna, in disguise, was discovered the next day. With his life on the line, he was coerced into signing an armistice agreement on May 14 that recognized the Republic of Texas. That treaty was swiftly rejected by Mexico and Santa Anna was deposed.

Texas Independence

Treaty of Velasco

Agreement executed by President Burnet and Santa Anna

Library of Congress

Subsequent to their Declaration of Independence, the Republic of Texas immediately turned to governance consistent with the democratic traditions of the United States. In the election of 1836, Sam Houston was elected president (1836-1838) and replaced David C. Burnet, the provisional president. However, the euphoria of independence was tempered by policy emanating from Mexico City.

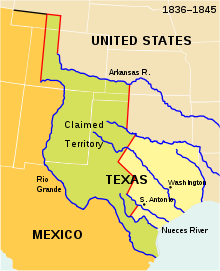

Boundary disputes were far from insignificant. Texas claimed the territories of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico. They fixed their southern boundary with Mexico on the Rio Grande River. Mexico countered with their northern boundary as the Nueces River---about 200 miles north of the Rio Grande. This last boundary dispute influenced the United States to declare war on Mexico (May 13,1846).

Internal politics were clearly defined between two parties. The Houston faction sought annexation by the United States and peace with the Indians, but successive U.S. presidents, Jackson and Van Buren cautiously ignored the Texas overtures.. The other party, led by Mirabeau B. Lamar, elected president of the Republic (1838-1841) sought expansion to the Pacific Ocean and open warfare with the Comanche Indians.

Texas Independence

David C. Burnet'

|

Samuel Houston

|

President Andrew Jackson recognized the Republic of Texas March 3, 1837. Maps displayed below reflect 1836 borders and as expanded by the Compromise of 1850. Many European nations followed with recognition of the new republic, but Great Britain maintained a balancing act between Texas and Mexico without official recognition of the former. Mexico refused recognition of the new republic, but never reasserted its civil administration in its former territory. Nevertheless, small, scattered military actions continued.

Texas Independence

|

|

Military action in east Texas was essentially confined to naval activity. Battles of the Brazos and Galveston Harbor were inconclusive other than Mexican unshaken resolve to refuse recognition.

In 1842, the cat with many lives, Santa Anna was again elected president. His eyes were always on lost Texas. He ordered army expeditions to cross the Rio Grande. By March his forces reoccupied Goliad and San Antonio, and inexplicably, the Mexican forces under General Adrian Woll abandoned San Antonio 10 days later. On September 11, Woll returned to San Antonio. His troops were ambushed by Texian militia on September 17 who were victorious at Salado Creek. Texian fortunes were reversed when General Woll's forces massacred 52 Texians known as the Dawson Massacre. Woll then withdrew to Mexico. Skirmishes between the forces were intermittent over the next several years until the final chapters of Mexican American history in 1846.

_______________________________________________________________

Sources:

Library of Congress

Mexican National Palace

National Archives

National Portrait Gallery

Sons of Dewitt County Texas

Star of the Republic Museum

Texas State Capitol

Texas State Library and Archives Commission

References:

Encyclopedia Britannica

Greenberg, Amy S., A Wicked War, Alfred Knopf, New York, 2012.

Marley, David F., Texan Independence, Wars of the Americas, ABC-Clio Inc. Santa Barbara, California, 2008.

Nardo, Don, The Mexican-American War, Lucent books, San Diego, California, 1991.

American Wars | Mexican American War | Texas Independence